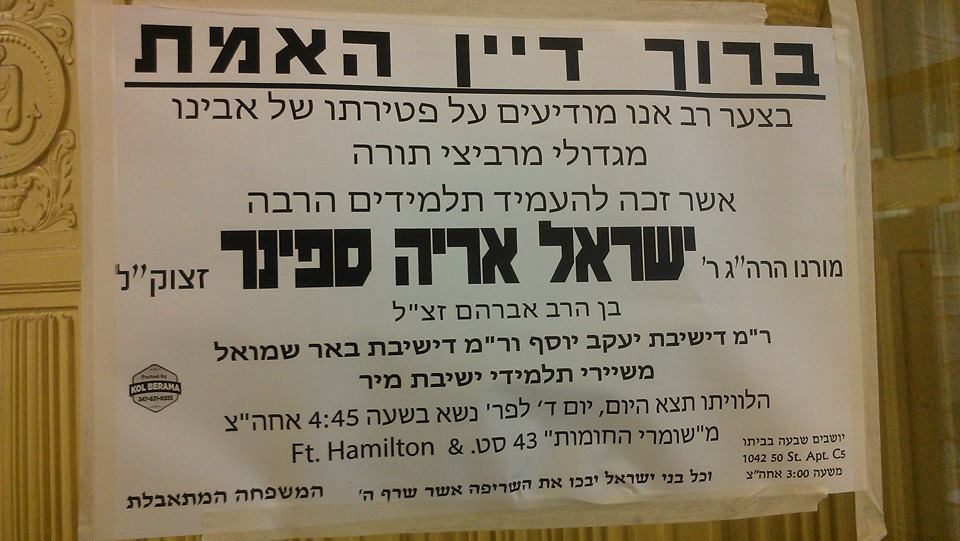

An Appreciation of the Alter of Slobodke by his talmid HaRav Meir Chodosh — “And they said, You have Revived us!”

The alter of Slabodka – Yarzheit 29th Shevat

by Moshe Musman

Introduction

The following recollections of the Alter of Slobodke zt’l offer a spiritual portrait of one of the greatest and most influential educators that the modern yeshiva world has known. As well as eminently qualifying him to elucidate the main ideas of the Alter’s outlook, HaRav Chodosh’s standing as one of his closest talmidim for over twenty years also qualifies him to demonstrate how the Alter himself was their embodiment.

From a close reading of the shmuess, herein it seems clear that in addition, HaRav Chodosh intends to show how the ideas which the Alter spread indeed addressed areas of general human weakness, such as the fear of sin and the importance of humility, with which a superficial acquaintance with Slobodke mussar, with its emphasis on inspiring and uplifting and their distinct outer manifestations, may have led outsiders to believe that the Alter was less preoccupied with than were the proponents of other mussar systems.

Indeed, the term gadlus ho’odom, the greatness of man or mankind, is not fully understood today. Many mistakenly associate it with a certain air of self assurance and style of clothing, as if this approach achieved the improvement of the self image of bnei Torah by having them dress smartly.

In this shmuess, HaRav Chodosh sets out the fundamental premise of gadlus ho’odom and shows how its correct appreciation and assimilation led to the realization of the main goals that all the different mussar systems shared. HaRav Chodosh demonstrates that attaining yiras Shomayim is the work of a lifetime and that success can only result if a person’s efforts are firmly founded upon a correct understanding of man’s purpose in this world.

To achieve this, the Alter continually drew upon Chazal’s teachings concerning the greatness of Odom Horishon. HaRav Chodosh goes on to show that the attainment of true wisdom and humility, as well as refined and pleasant character traits, are both an outgrowth of recognizing man’s relationship with his Creator.

Obviously, this awareness will also require that interpersonal relationships are handled with the utmost consideration for others. An understanding of the soul of Slobodke mussar enables its outward features to be viewed in their proper proportions. Why didn’t the Alter write seforim? Why was he continually speaking about Odom Horishon? His home was open to all, twenty-four hours a day, yet he lived a life of modesty and concealment. He was speaking all day, yet he was a man of silence. Why did he speak softly, so that people had to move closer in order to hear him? Why did he hold onto a handkerchief or cloth during a shmuess? Some of the enigmas about the Alter are explained herein.

The shmuess was delivered by HaRav Meir Chodosh on the twenty ninth of Shevat, 5741, the Alter’s yahrtzeit, in the beis haknesses of Hisachdus Yeshivas Chevron in Bnei Brak. It was transcribed by Rabbi Aharon Meir Kravitz, who is a grandson of HaRav Chodosh.

Write Them On Your Heart! In the Torah world at large and especially in the yeshivos, the day before Rosh Chodesh Adar is a day of introspection.

This day marks the yahrtzeit of the man who founded our holy yeshiva — not merely with regard to its material founding but also in the sense of having put the yeshiva upon its feet, educating and guiding us so that we developed spiritually. He taught us to tread along the path of Hashem, [and showed us] an approach to serving Him. The Alter left his Torah in oral form. He didn’t record his novel ideas in writing.

On his way to Eretz Yisroel he travelled through Berlin and went to visit one of the greatest of his talmidim, who was one of the renowned rabbonim of the generation. The talmid asked his rebbe, the Alter, why he did not record his [many] shmuessen, since the Alter used to lecture day and night. The talmid related that several other distinguished talmidim of the Alter’s had been with him earlier and he had asked them what the Alter had been speaking about lately.

By way of answer, they had tried to repeat two or three shmuessen, but they couldn’t remember a fourth one. Since it seemed that the shmuessen were being lost, why didn’t he keep a written record of them? The Alter answered him with another question. “You have conversed with my talmidim — are they the same as other people?” “No, certainly not. The difference is recognizable at once.” “Those are my shmuessen,” the Alter replied. “They are written down on my talmidim!” I then asked that rav, “They must have told you the most recent shmuessen, which he delivered before leaving for Eretz Yisroel.

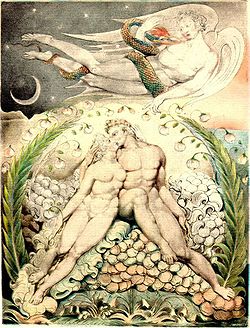

One of them concerned the greatness of man, portraying him as being greater than a mal’ach, from whom the mal’ochim [themselves] had to learn, as HaKodosh Boruch Hu said to them, `See the creation that I have made, whose wisdom exceeds yours . . . ‘ [Yet] although Hashem told the mal’ochim to contemplate Odom Horishon’s wisdom, they couldn’t learn from him in the ordinary way, like a talmid from his rebbe.

The gemora (Sanhedrin 59) says, `Rabbi Yehuda ben Teima says, Odom Horishon reclined in Gan Eden and the mal’ochim roasted meat and strained wine for him . . . ‘ The only way they could take something from him was by serving him — they were able to grasp something by performing tasks connected with the preparation of his food — this shows us the greatness of Odom Horishon.”

And indeed, this was one of the shmuessen which that rav had heard from the talmidim. “However,” I told him, “that shmuess did not just represent one single shmuess. In order to appreciate a shmuess like that about Odom Horishon, one has to first hear a number of other introductory shmuessen: about the Creation and why it was made, about the meaning of the `wisdom’ which Hashem rated as being greater in Odom than in the mal’ochim and what the level of Odom Horishon’s wisdom actually was.

Only then [can one understand a shmuess about] who Odom Horishon was and in what way `his wisdom exceeds yours.’ [For example,] if one asks a young child what he is learning, he will first say `alef- beis.’ If one asks him later on, he’ll tell you `Kometz alef: oh,’ and later on he’ll answer that he is learning to read sequences of letters. Later still, he’ll say he’s learning to read from the siddur but he won’t mention that he’s learned `alef-beis, kometz alef: oh’ and the earlier stages, because all that is included in having learned to read siddur.

“On a later occasion, I told the rosh yeshiva, HaRav Yechezkel Sarna zt’l, that in responding to that rav by asking him whether the Slobodke talmidim were the same as others, the Alter intended to convey the message that his shmuessen actually were being recorded, in the sense of the posuk, `Write them on the tablet of your heart.’ The principle record is the one that gets left upon the heart. The Alter therefore `wrote’ upon thousands of hearts, building them and guiding them in the service of Hashem.”

The Foundation of Yirah He was continually involved in the profound topic of man’s greatness. At first, his reason for speaking about Odom Horishon at such great length was a total puzzle to his talmidim, however, in time we understood, as we shall explain. It is a very widespread error to think that yiras Shomayim is a more straightforward and self evident acquisition than Torah knowledge.

People know that learning Torah is necessary in order to understand [Torah], yet when it comes to the special wisdom of the fear of Heaven, everybody supposedly knows all about it and understands what it is by themselves. The truth however, is otherwise. In his introduction, the Mesilas Yeshorim protests the practice in his times, when only those with coarse minds involved themselves in the study of yiras Shomayim.

Those who found it hard to learn Torah, studied works of mussar and became mussar-niks, whereas those with swift comprehension, who possessed sharp, intelligent minds, did not spend time on this field of study, arguing that it was all simple and well known. The Mesilas Yeshorim introduces the idea that true fear of Heaven is one and the same thing as wisdom. It therefore follows that when people imagine they know what yirah is, that can’t be true yirah, about which the posuk says, “If you seek it like silver and hunt for it like hidden treasure, then you will understand the fear of Hashem.” [The Mesilas Yeshorim points out that,]

“It doesn’t say `Then you will understand philosophy, then you will understand engineering . . . medicine . . . dinim . . . or halochos . . . It says, `Then you will understand the fear of Hashem.’ You see that in order to understand yirah, one has to seek it like silver and hunt for it like hidden treasure . . . ” Later on, in the first chapter of Mesilas Yeshorim, he begins to explain the foundation of yirah, thereby demonstrating to us that it has a foundation.

And if there needs to be a foundation, it follows that where it is lacking, anything that is built there will have no permanent existence. If someone possesses yirah but his yirah lacks a foundation, the entire edifice is in danger of collapse. And what is that foundation? “The foundation of piety and the root of the perfect service [of Hashem, the Mesilas Yeshorim tells us,] is that a person’s duty in his world should become distinct and authentic to him.”

Chazal have taught us that man was only created in order to find pleasure in Hashem. It therefore follows that the foundation of the entire study of yirah is the knowledge that man was only created to enjoy Hashem. It isn’t enough to know that one is supposed to enjoy Hashem — such knowledge is insufficient to serve as a foundation for piety and serving Hashem; the basis is still lacking.

One has to know that this is the only purpose for which man was created. Included in the foundation of yiras Shomayim therefore, is the study and the understanding of the true purpose of man’s creation. That is the reason why the Alter was always involved in and always spoke about this profound topic. He literally lived it and continued developing new insights into it throughout his life. When one appreciates what man is, what Odom Horishon’s greatness was and [the extent of] his descent from that level after he sinned, one can then appreciate the extent to which sin is the opposite of having pleasure in Hashem. [One can understand] how much one ought to keep one’s distance from the slightest trace of sin, so as not to lessen one’s greatness.

Raising Oneself to the Torah’s Standards That is [also] why he always used to speak about the quality of the Torah that was given from Heaven. That Torah was given to man; therefore man has to tailor himself to the Torah. Man must scale ever greater spiritual heights, so that he is worthy of Torah, rather than making Torah suit him as he is. He must place obligations upon himself, so that he becomes deserving of learning Hashem’s Torah.

This idea is expressed by the mishna (Sanhedrin 33): When witnesses come to testify against a murderer, they are first intimidated, so that they will relinquish any ideas of basing their testimony upon anything but the facts.

They are asked, “Perhaps you are basing yourselves on circumstantial evidence or on hearsay . . . ?” and they are taught the severity of putting a person to death without the full requirements of the Torah’s law having been met. They are told, “This is why man was created as an individual; to teach you that whoever destroys a single Jewish soul, is considered . . . as having destroyed an entire world.” [The single soul of whose importance we call the witness’s attention is his own.]

“Therefore, every single individual must say, `The world was created for me,’ which Rashi explains to mean, “I am as important as an entire world; I won’t trouble myself out of the world for the sake of a single sin,” and he will desist from it.” In order to dissuade someone from testifying falsely — perhaps he has some partiality and because of it he won’t tell the truth — we threaten him, and without this intimidation, we don’t accept his testimony.

What is it that we convey to him? That he ought to have a proper estimation of his own importance and greatness, so as not to chas vesholom trouble himself from the world on account of a single sin. Man was created to have pleasure in Hashem, while sin distances him from this pleasure. If man but understood what his potential is and how the sins which he does affect him, he would refrain from sinning.

Chazal understood that only by fully appreciating this will a man refrain from testifying falsely. These are realizations which must not remain as theoretical knowledge; they must become part of life. This is something which we continually witnessed about the Alter. He lived these ideas and spent his entire life in the contemplation of the purpose of Creation and the consequences of sinning.

He also used to speak at length about how teshuvah is apparently the opposite of having pleasure in Hashem, for teshuvah is based upon regret. Nevertheless, that too is having pleasure in Hashem, for a person is led back to that state by dwelling upon the Creation, upon man, upon sin and teshuvah and upon the greatness of man’s power to return to his original level.

Fitting Behavior in the King’s Presence Rabbenu Yonah (in Sha’arei Teshuvah, sha’ar III:27) writes, “One of the Torah’s prohibitions which is dependant upon [the thoughts and feelings of] a person’s heart is, `Guard yourself, lest you forget Hashem your G-d’ (Devorim 8:11) . . . We are hereby warned to remember Hashem at all times. [Therefore,] a man must try to acquire the constant presence in his soul of those traits which are consequences of this remembrance, such as yirah, modesty, refinement of one’s thoughts and the regulation of character traits; for the members of the holy people will attain every becoming attribute which beautifies its owner, through remembering Hashem Yisborach, as the posuk (Yeshaya 45:25) says, “In Hashem [i.e. by remembering Him at all times,] all the seed of Yisroel will attain righteousness and be praised.”

From this posuk, Rabbenu Yonah shows us that constantly remembering Hashem confers the obligation to elevate oneself and to attain every becoming trait: yirah, modesty and the perfection of one’s thoughts. We witnessed all this in the Alter. On every single occasion, he would demand that our conduct be based upon wisdom; “Hashem founded the world with wisdom,” (Mishlei 3:19).

He always used to say, “Don’t be like horses, like uncomprehending mules,” (Tehillim 32:9). The major portion of one’s yirah had to be exercised together with one’s wisdom, while at the very same time, all of one’s wisdom had to be invested in one’s yirah. All of his own tremendous wisdom was encapsulated within his yirah, as the mishna (Avos 3:21), says, “If there is no wisdom there is no yirah; if there is no yirah there is no wisdom.”

The modesty with which he conducted himself was amazing. His home was never a private place. It was a public domain. There were talmidim coming in and out at all hours of the day and night. He never closed his door, not even while he ate or slept. This would seem to be a contradiction to modesty, for while a person is in the company of others, he cannot conceal himself.

However, by appreciating his greatness, it was possible to understand how much of it was hidden and concealed by his modesty. This trait is mentioned by the gemora (Makkos 24), “Michah came and summed them up in three principle requirements as the posuk (Michah 6:8) says, `He has told you, man, what is good and what Hashem your G-d requires from you, [it is] but to do justice, to love doing kindness and to go modestly with your G-d.” One of the foundations of yirah is therefore modesty.

One might have thought that a person only needs to conduct himself modestly when he is engaged in activities that are usually done privately, but this is not required when doing things that are anyway normally done in public. However, the gemora continues, `And going modestly — this refers to taking out the dead and bringing in the bride.” Rashi explains that the word leches, going, is used by the posuk (Koheles 7:2) in speaking of both these occasions.

We therefore see that modesty is a requirement even when doing things that involve `going.’ The gemora concludes, `If the Torah tells us about `going modestly’ even when doing things that are not usually done in private, how much more so is this necessary with those things that are.’ Further explanation of the modesty necessary in escorting the dead or a bride, is provided by Rashi on the gemora in Succah (49), which brings the posuk (Shir Hashirim 7:2), “Your thigh is concealed — Why are words of Torah compared to a thigh? To tell you that just as a thigh should be concealed, so too should words of Torah.”

The gemora then goes on to quote Rabbi Elozor, who brings the posuk from Michah, with the requirement to exercise modesty. Rashi explains that, “Even there, [when accompanying the dead or a bride,] modesty is necessary, to eulogize to a fitting degree and to rejoice in a fitting degree . . . ” The Alter would always speak about how to travel to a wedding in the correct manner and how to gladden others there in a becoming manner, and it was this gemora that he had in mind. He worked [on himself] in this area.

Although there was not a moment when he was alone, he nevertheless succeeded in concealing himself. All his own yirah was covered and concealed. When he spoke about yiras Shomayim, he would refer to it as wisdom — but in fact he meant yirah and the perfection of one’s thoughts. It was well known that when one was in his company, one had to pay attention to how and what one was thinking, [and one had to act] with beauty and with grace, as in the posuk which Rabbenu Yonah quotes, “All the seed of Yisroel will attain righteousness and be praised in Hashem.”

This is the level which a person ought to achieve, as Rabbenu Yonah explains: remembering Hashem confers an obligation to elevate oneself and to attain every fitting attribute that adorns its owner. He always demanded that his talmidim become aware of and fully estimate man’s greatness. Every single one of a person’s thoughts has tremendous worth, how much more so every word that he says. How careful ought one to be to avoid anything that cannot be considered a “refinement of thought.”

A Lifetime’s Craft This is why one of the foundations of his education was the lesson of the gemora (Chulin 89), “Rabbi Yitzchok said, `What is the meaning of the posuk (Tehillim 58:2), “Have you truly been struck dumb . . . ?” — What should a person’s craft be in this world? To render himself [as though he were] struck dumb.” The gemora’s use of the term “craft” implies that creativity is necessary in practicing this and that one needs to study ways to be creative.

It [also] implies that this pursuit is the main object of life, as the gemora says at the end of Kiddushin, “A man must teach his son a craft.” Man’s craft and his task in this world is to render himself speechless. The gemora goes on to say, “Perhaps this also applies to words of Torah? The posuk says [however,] `speaking justice.'” We see that a special teaching is needed to tell us that one can speak words of Torah.

Without this, absolutely all speech would have been proscribed. This shows us the power of human speech and how carefully we have to guard it. There seems to be a difficulty though. If one is supposed to speak words of Torah, one should be speaking all day long, in which case, how can one ever remain speechless? The Alter taught us however, how one can be speaking all day and yet remain silent.

We saw with our own eyes how he talked and talked without end, all day long, raising thousands of disciples with his words, yet he nevertheless remained silent. We saw how with every word that he uttered, it was as though a dumb man’s mouth had been opened. It looked as though a dumb person had suddenly managed to start speaking.

This was how it always appeared. Even outside the yeshiva, when he spoke to strangers, to gentiles or to anyone else, every word he uttered seemed to have been forced from the lips of a dumb man. Any superfluous word was certainly unthinkable. He would always mention the posuk (Iyov 28:12), “And from where will the wisdom be found?” making a play on the word mei’ayin, from where and explaining it as a negative, meaning, from what is not.

In other words, there is wisdom to be extracted from what is not said. A large amount of what the Alter taught us came from what he did not say, just as entire Torah discourses have been based upon things which the Rif did not include in his digest of halacha. The Alter never allowed himself to escape the sensation of being unable to speak. The Alter used to speak quietly, and all the bochurim had to crowd round him in order to hear.

Often, they had to rest their heads right upon their friends’ heads, just to be able to hear him. Once they asked him to speak in a louder voice and they could see that he was trying and trying but it didn’t help — after all, he was like a man who has been struck dumb. During shmuessen, he would always be holding a handkerchief or a cloth, at which he would be humbly looking.

At one time, I thought that this practice was in keeping with the Ramban’s advice, that when one reproves someone else, one should not look at him directly. However, I heard from the gaon HaRav Yaakov Kamenetsky [zt’l,] that the Alter told him that it was because he had a shy nature and he was not used to looking people in the face. Yet, with all his bashfulness, his modesty and his great humility, and while he conducted himself as though he was dumbstruck, he still managed to raise thousands of talmidim, literally building them up.

This was his strength — he was able to remain concealed and silent, yet be such a prolific educator. It is impossible to transmit this quality merely by word of mouth. One has to see an example. Then one can learn from it what one cannot glean from shmuessen alone. The foundation of all this was “the greatness of man” — that was always the basis. In the Divine Likeness We find that when HaKodosh Boruch Hu came to give the Torah to the Jewish nation, His principle [prefacing] command was, “And you shall be a treasure for Me,” (Shemos 19:5). Everything was founded upon this, including the actual receiving of the Torah.

Afterwards too, He told them, “You have seen that I spoke to you from the Heavens.” The posuk continues, “You shall not make [what is] with me; you shall not make for yourselves gods of silver and gods of gold.” Rashi explains that this prohibits making Keruvim like those in the Beis Hamikdosh, to place in botei knesses and botei medrash.

This is denoted by the word “lochem, for yourselves” meaning that even Keruvim, which are certainly not intended to be for idol worship chas vesholom but to facilitate the presence of the Shechina, are considered idolatrous if they are made elsewhere. In what area is it permissible for man to add to and expand his service of Hashem? Only [through offering voluntary sacrifices] upon the “mizbei’ach of earth” which “you shall make for Me.” This is the only way.

However [here] there is another condition, to which careful attention should be paid. “You shall not ascend my mizbei’ach on stairs, [so] that you do not reveal your nakedness over it.” Rashi explains that when going up stairs, one needs to take wide steps and even though the cohen remains covered, because the Torah commands that he wear trousers, opening the legs wide is akin to revealing oneself.

This denotes a belittling attitude towards the mizbei’ach. Rashi then quotes Chazal’s reasoning that if the Torah is so demanding concerning inanimate stones, simply because they have a purpose — although they remain unaware if something shameful is directed at them — how much more so ought we to be concerned to avoid shaming a fellow man, who is created in Hashem’s image and who cares greatly about his shame.

Let us consider this more deeply. When one wants to fashion inert metal into Keruvim — not for avoda zorah but for serving Hashem — this retains the appearance of idolatry, with the sole exception of the Beis Hamikdosh. When it comes to a human being however — Hashem’s handiwork, the purpose of Creation, for whom the entire world was made, whom the posuk tells us is made in the likeness of his Creator — the obligation is far greater: to be aware of and to act in accordance with the knowledge that a fellow man is a likeness of the Creator and to look upon him as though one were looking at the likeness of the Divine, as it were.

[The worth of a human being is so great that it supersedes any “appearance” of idolatry.] All this applies to other humans, despite the fact that to relate to any other kind of object in this way is utter idolatry chas vesholom, even if one doesn’t imagine there is any likeness to Hashem (as in the case of the Keruvim, that are made only to facilitate the presence of the Shechina.)

We see here what value the Torah places on a person’s self respect. Yet there is still another point to consider. The Torah’s warning to a cohen not to behave disrespectfully when serving Hashem on the mizbei’ach, is apparently limited to the duration and the place of the actual avoda, as the posuk specifically states.

What grounds are there for applying it universally to one’s fellow man? We must therefore conclude that the Torah places greater value on a person’s honor than it does on that of the mizbei’ach, to the point where the former can indeed be learned from the latter through a kal vachomer.

Know Your Purpose! Understand Your Importance! This is the foundation of “the greatness of man.” As a result of contemplating this profound topic — which encompasses the ultimate purpose of Creation as well as the basis of the fear of Heaven, as we explained earlier from the words of the Mesilas Yeshorim — [one will know] how to value one’s fellow man properly and how to respect him. One will also be aware of how carefully his dignity should be preserved, so that one does not chas vesholom assail the honor of the likeness of Hashem.

This is the day’s message: [appreciate] each person’s worth and the importance of each and every action. This was what we saw in the Alter, how he weighed every movement and every step that he took. I once travelled with him on vacation. I wanted to see how he would conduct himself outside the walls of the yeshiva. I saw that nothing changed in the slightest, neither in the way he arranged his day, nor in the way he spoke.

One cannot be a yirei Shomayim without studying the Creation and Odom Horishon, so that one knows what the world was created for. This knowledge is the foundation of yirah and the wisdom with which it must be invested. It must be delved into deeply and contemplated, so that one becomes sensitive to the lessons it imparts.