IN-DEPTH FEATURES

The Vilna Gaon: A Man of Piety

by Rav Dov Eliach

In his three-volume work HaGaon (that was put together under the supervision of HaRav Chaim Kanievsky) Rav Dov Eliach brought together an enormous amount of material to try to give us some concept of what the Vilna Gaon was. The Gaon was outstanding in many aspects of human development. Our concepts do not do justice to what the Gaon really was. The section printed here is taken from Chapter Six, and is centered around the piety of the Gaon. When reading it, one should keep in mind that this is just one of many areas in which the Gaon lived at a such an outstanding level.

This year Rav Eliach has added a new series of volumes to the bookshelf of works related to the Gaon with the publication of Chumash HaGra, an arrangement of the comments of the Gaon arranged according to the parshiyos of Chumash, with the full Chumash text. So far Shemos has appeared, and we eagerly await Bamidbor.

The Chazon Ish wrote of the Gaon: ” . . . his level of Divine inspiration and the like, and his diligence and breadth of knowledge, in profound depth, in all the Torah — we cannot imagine how it is even possible.” After reading this material one can say the same thing about the Gaon’s level of piety.

Beyond the Letter of the Law

During the Gaon’s famous self-imposed exile, he was once hosted by a certain family. The baby suddenly began to cry loudly, but none of the family members heard her, so no one responded. Seeing this, the Gaon approached her cradle and tried to calm her. As he rocked the cradle, he sang a very popular lullaby. The song, called “Sleep, My Child,” included the words, “And I will find you an appropriate bridegroom.”

Years later, when the girl had grown up and reached marriageable age, a young Torah student arrived one day at their home bearing a letter from the Gaon. In the letter, the Gaon said that they need not accept his proposal, but since he had uttered the sentence, “And I will find you an appropriate bridegroom,” he was suggesting the young man who was the bearer of the letter.

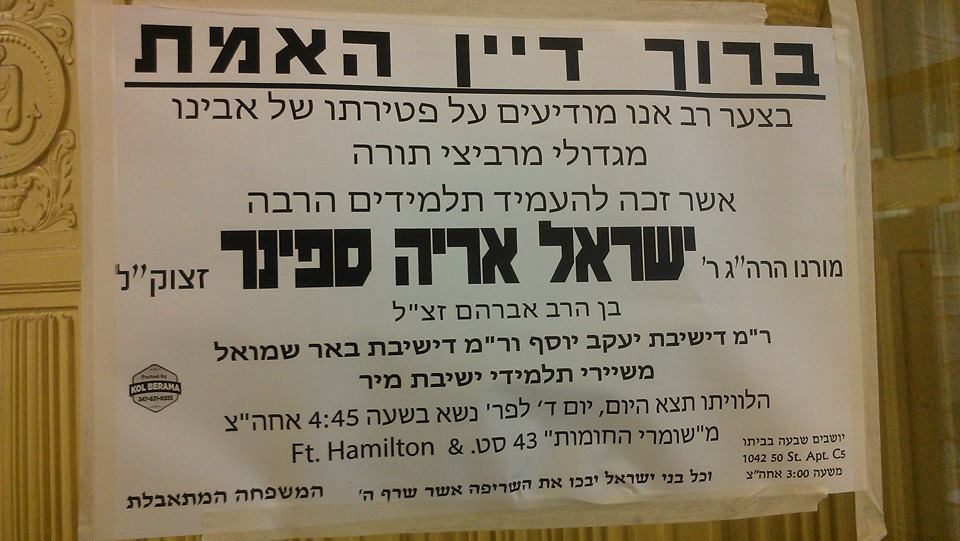

In concluding the letter, the Gaon reiterated that they need not accept the suggestion, but that he saw fit to fulfill his obligation by presenting this young man who, in his opinion, seemed to be a fitting match. The family saw that it was, indeed, an appropriate suggestion — and there could certainly be no better matchmaker — and so they agreed to the match. (Heard from Rav Yisroel Spinner, who heard it from his rebbe HaRav Chaim Shereshevsky, who heard it from his father, who heard it from HaRav Chaim Soloveitchik.)

This is an example of how far the Gaon went, well beyond the letter of the law. He had never promised the family anything, but since he had uttered those words, even though they were not meant to be taken seriously but merely to quiet a crying baby, the Gaon considered them a promise that should be kept.

Once, on a trip from his home in Vilna, the Gaon lodged at the home of a certain honest man. The host served him supper. The Gaon took a bite of the food, but his stomach was upset that day, causing him to retch immediately. When the host returned and saw the full plate of food, he urged the Gaon to eat. The Gaon again put some food into his mouth, and again he retched. This repeated itself a third and fourth time. One of the Gaon’s greatest disciples was with him at the time. He asked the Gaon why he was torturing himself in this way, since it was obvious that he was unable to eat.

The Chofetz Chaim heard about another episode from the Gaon’s period of exile from a student of the Gaon. One day, the Gaon hired a Jewish wagon driver. During the journey, the horse bolted from the path and galloped into a field, crushing plants beneath its hooves. The owner of the field, a coarse gentile farmer, noticed what happened and ran over to the wagon in a fury. In the meantime, however, the wagon driver disappeared, so the farmer rained his blows upon the Gaon, whom he found still sitting in the wagon.

The Gaon’s first thought was to retort, “What have I done to deserve your wrath? It was the wagon driver who failed to control his animal properly.” But he immediately strengthened himself and was silent.

The Gaon later remarked that had he said what he initially wanted to say, he would have been informing (mesirah) on the wagon driver. The Chofetz Chaim explained that according to the halacha, the wagon driver was probably not responsible to pay for the damage caused by his animal, and even if he was obligated to pay, he did not deserve to be beaten. By implicating the wagon driver, the Gaon would have been inciting the gentile against an innocent fellow Jew.

The sin of being an informer is so great, added the Gaon, that had he transgressed it, he would have been forced to be reincarnated as a dog, and all his Torah and mitzvos would not have sufficed to save him (Shem Olom).

The Gaon responded that the Sages said, “All that your host tells you [to do], you must do” (Pesochim 86a). Whenever it says, “You must do (aseh),” even concerning a Rabbinic commandment, you must try up to the point where it becomes life-threatening (Introduction of his sons to the Bi’ur HaGra on Shulchan Oruch. HaRav Shlomo Brevda reported that the Chazon Ish was skeptical if the story is true. However, in Me’ir Einei Yisroel a similar story is told about the Chofetz Chaim.).